Ta-Nehisi Coates's Courage

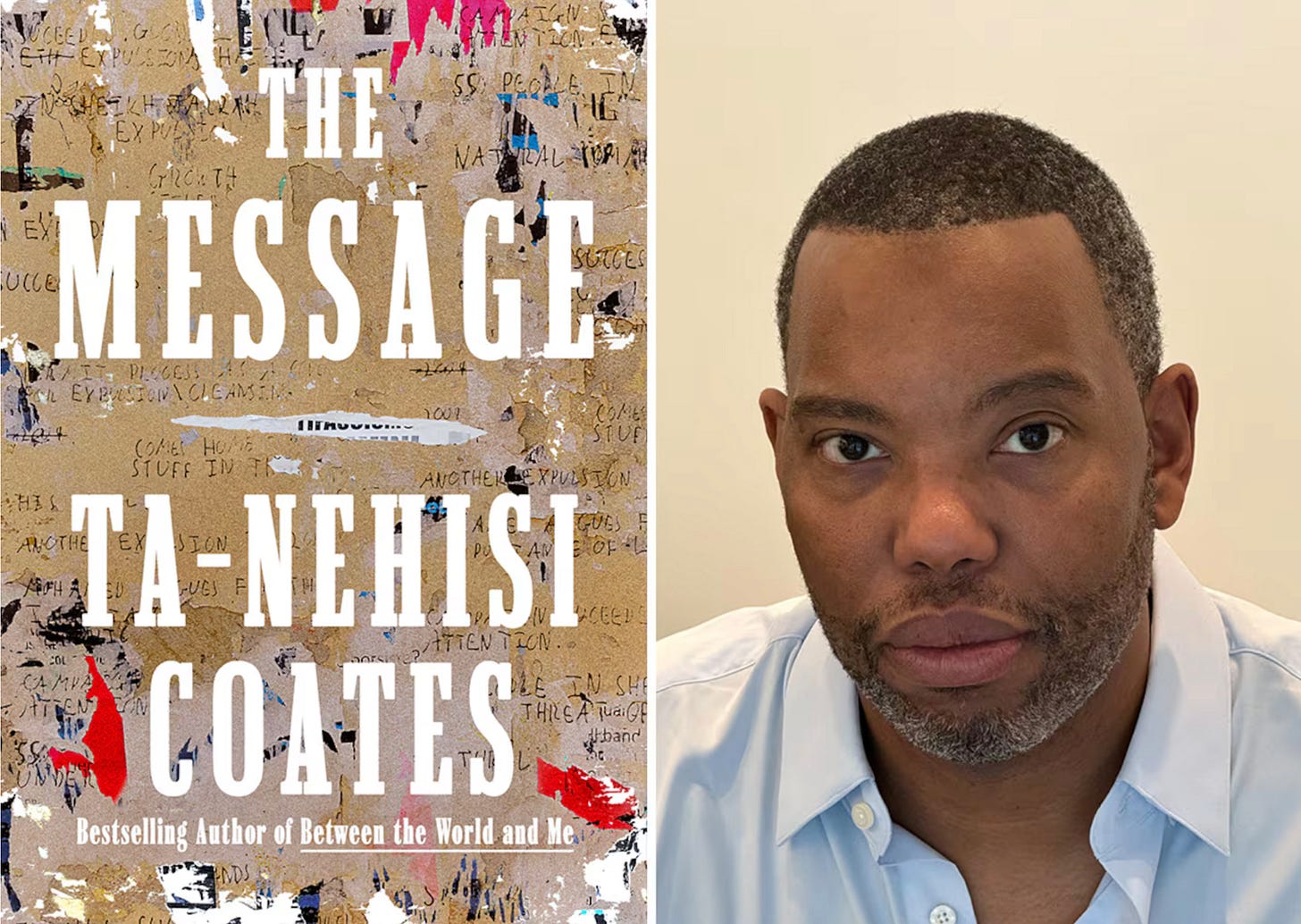

This Thursday at 11 AM Eastern, I’ll be interviewing Ta-Nehisi Coates about his new book, The Message. Coates’ decision to write unsparingly about Israel’s oppression of Palestinians— in full knowledge that doing so would turn many of his former admirers into adversaries— is among the most remarkable things I have seen an American writer do. I made a short video relating Coates’ decision to a speech about writing and loneliness that Albert Camus gave in 1957.

If you become a paid subscriber, you can watch my conversation with Coates live this Thursday. You will also get the video/audio of our conversation the following week. Once you’ve upgraded, you’ll be able to open the previous post for this event and use the registration link there.

Space could fill up, so to those who are interested, I’d recommend registering soon.

Hope to see you on Thursday,

Peter

VIDEO TRANSCRIPT

So I'm interviewing Ta-Nehisi Coates on Thursday, and I wanted to say something about the significance of his new book, The Message, and particularly about the fact that he devotes so much of it to the cause of Palestinian freedom.

Ta-Nehisi Coates, is maybe the most celebrated political writer of our time. And, for reasons that I think are complicated to understand, despite the fact that his critique of American society has been very profound, liberal America, obviously not conservative right-wing, but mainstream liberal America, really opened itself to him, his critique, and really celebrated him, and he had the the acclaim of a celebrity, this aura and status of celebrity, I think, unlike any other political writer that I can think of in our time.

And he's written about celebrity and how dangerous it is. And I've had a tiny, tiny taste, 1/1000th of that, and I know how seductive it is, and how seductive it is to be close to power, and to have people who are really powerful and important think you're great, and want to hear your position and invite you to exclusive things. And it's really hard to to turn that away, and I would imagine, although I don't know for sure, even harder if you're Ta-Nehisi Coates, who did not grow up in privilege, who grew up profoundly aware that it was only by some miracle, in some ways of fate, that he came from where he did to that position. Obviously his own enormous talent, but the odds were so stacked against him, to have achieved that pinnacle of celebrity and acclaim throughout mainstream liberal America, and then to take on probably the one subject in American politics, or one of the very few, that you know is guaranteed to lose you a lot of that, because many of the same powerful mainstream, liberal- or centrist-minded people who were very happy and fine to accept what you wrote about race, fine to accept what you wrote about reparations, and would have been fine to accept your writing about all kinds of stuff, that this was the subject, Palestinian freedom, humanity, Israeli oppression of Palestinians, the one thing you knew was going to sacrifice a lot of that. And yet Ta-Nehisi Coates walked straight into that, willingly, because of a sense of moral obligation. And I've been thinking a lot about whether this has created a sense of isolation for him because now will be isolated from people who previously feted him. But I also wonder whether it might produce the opposite. And I started thinking about that when a friend sent me this speech by Albert Camus, his Nobel Prize acceptance speech in 1957. And this is what Camou says. I think it's very, very relevant to Coates, his position in this moment.

Camus says "The writer's role is not free from difficult duties, by definition. He cannot put himself today in the service of those who make history. He is at the service of those who suffer it. Otherwise he will be alone and deprived of his art. Not all the armies of tyranny, with her millions of men will free him from his isolation."

And then he goes on to say, "His art must not compromise with lies and servitude, which, wherever they rule, breed solitude. Whatever our personal weaknesses may be, the nobility of our craft will always be rooted in two commitments, difficult to maintain: the refusal to lie about what one knows, and the resistance to oppression."

Ta-Nehisi Coates's refusal to lie about what he saw in the West Bank, first to go there right? Because so many people, so many celebrated people in American public life, choose not to go there. Because they know, at some level, that if they went there, then they would be forced to carry around the secret that they don't want to have to face the consequences of exposing. He purposely went to see it, and then decided to write about what he had seen. And I think what's so fascinating to me about Camus' words is that Camus kind of turns this on its head, and he said, actually the deepest form of isolation that a writer can face is not the isolation of being shunned by people in power. It's the isolation of being isolated from your craft by being isolated from the truth.

The deepest form of loneliness is not the loneliness of someone who is no longer feted by those in authority. It's the loneliness of someone who's not speaking their own truth. And so, perhaps the message of Camus is that actually the deepest form of community that you have is when you're actually willing to say the things that you believe are true, even if that puts you in community with people who you don't know, who you can't see, who certainly don't have the power and the cultural status, to celebrate you in the way that people in power do. That's a much deeper sense of community. And it's the alternative, betraying your commitment to the truth and your commitment to your values, that ultimately produces isolation.

And so that in that sense, what Ta-Nehisi Coates has done actually, is in some ways created a deeper sense of connection with so many people, and even though his role in American public life will change because of this book, I can really think of no one in American letters who is more living the spirit of what Camus asserts that writers should do in that speech than Ta-Nehisi Coates has done, and it's part of the reason I'm so pleased to be speaking with him on Thursday, and I hope you'll join us.

Thank you fro your courage Peter. As an American Jew whe came of age in the 1960's and 1970's in a Jewish community, I went to Hebrew School three times a week, was Bar Mitzvah and walked around my neighborhood canvassing for the Jewish National Fund. I learned many myths about the founding and growth of the state of Israel, which was purposely connected to what it meant to be Jewish. I read the autobiographies of Abba Eban and Golda Meir. I learned some painful lessons over the succeeding ears about the real founding and development of Israel, quite by accident. As an undergraduate student at U'Mass, I decided to write a term paper on "human rights" and came across the works of Noam Chomsky. What an awakening. Since then, I have had the pleasure and privilege of reading Norman Finkelstein ("Gaza and the Misuse of Anti Semitism") Edward Said, Illan Pappe and many more courageous Jews like you. I'm now an immigration lawyer in Falmouth, MA, on Cape Cod, after practicing criminal law for many years. We have a very active ceasefire organization hereand have put on a number of well attended educational forums featuring Rabbi Brian Walt and Alice Rothschild.

We need to do more. I just wanted to say:Thank you, thank you, thank you. If you are ever in Falmouth on the cape, don't hesitate to pay us a visit. We live on a wonderful bike path a stone's throw from the harbor and beaches. Keep up the good work and I look forward to the Ta-Nehisi Coates interview.

Peter, thank you for your kind, thoughtful profile of Ta-Nehisi Coates, writers as truth-tellers, and what they face when they tell their truth. Very much looking forward to your interview this Thursday.